Join Professor Aldo Faisal, a leading expert from Imperial College London and Director of UK government-funded AI centers, as he explores the transformative power of AI in healthcare. This keynote takes you through the evolution of AI, revealing how unconventional data sources like shopping patterns and timestamped patient records can enable earlier, more accurate diagnoses. Discover how AI is enhancing clinical decision-making, optimizing treatment strategies (like in sepsis management), and the critical need for human oversight and continuous learning in AI systems. Professor Faisal also introduces the groundbreaking Nightingale AI initiative, aiming to build a large-scale health model that thinks like a clinician.

Presented by:

Aldo Faisal, Professor of AI & Neuroscience, Director, School of Convergence Science in Human & Artificial Intelligence, Director, UKRI Centres in AI for Health, Imperial College London

Video Transcript

Below is the full transcript of the READY2025 Healthcare Solutions Keynote featuring Professor Aldo Faisal.

[0:00] Good morning everyone. I see you’re all nice and perky. To your big surprise, I’m going to deliver a keynote on AI, and some may roll their eyes, as I did about 10–20 years ago when I started working in machine learning and thought that was the future. There was this other group of people who were doing AI, which was seen as the old-school thing, while machine learning was the real thing to do.

That goes back to a long story about how we actually create innovation. If you think about it, we can go all the way back when our ancestors learned to make fire. And since that that moment to today, the way we innovated was that a few smart people sit down, tinker, and build the solution

[0:48] Then came a time around the late 80s and early 90s when people started to think: can we build systems that learn to solve problems for which humans need intelligence? But instead of building the systems themselves, we enable them to learn from data to discover the solution on their own. That’s the approach of machine learning, and it has become the dominant way by which we are now designing and building AI systems.

[1:17] If you ask me to this day, “Do you do AI?” I say no, I don’t do AI. AI is what you do with PowerPoints. I do machine learning—that’s what you do with Python. Coming from that perspective, I want to tell you a bit about the journey we’ve been on over the past ten years, when we started working on AI for healthcare and began to started to embrace agency in a systematic manner

Read the full transcript

[1:29] I’m a professor at Imperial College London and director of the two UK AI centres in AI for Healthcare and AI for Digital Health. They constitute the largest single investment by the UK government in science research for artificial intelligence in general, and we’re delighted that we were successful in getting that focused on healthcare.

Our partners are not just the National Health Service, but crucially—and fairly uniquely—we brought in the UK healthcare regulators as partners in our center, as well as over 40 industry partners. Over the past few years, we’ve managed to realize a number of things.

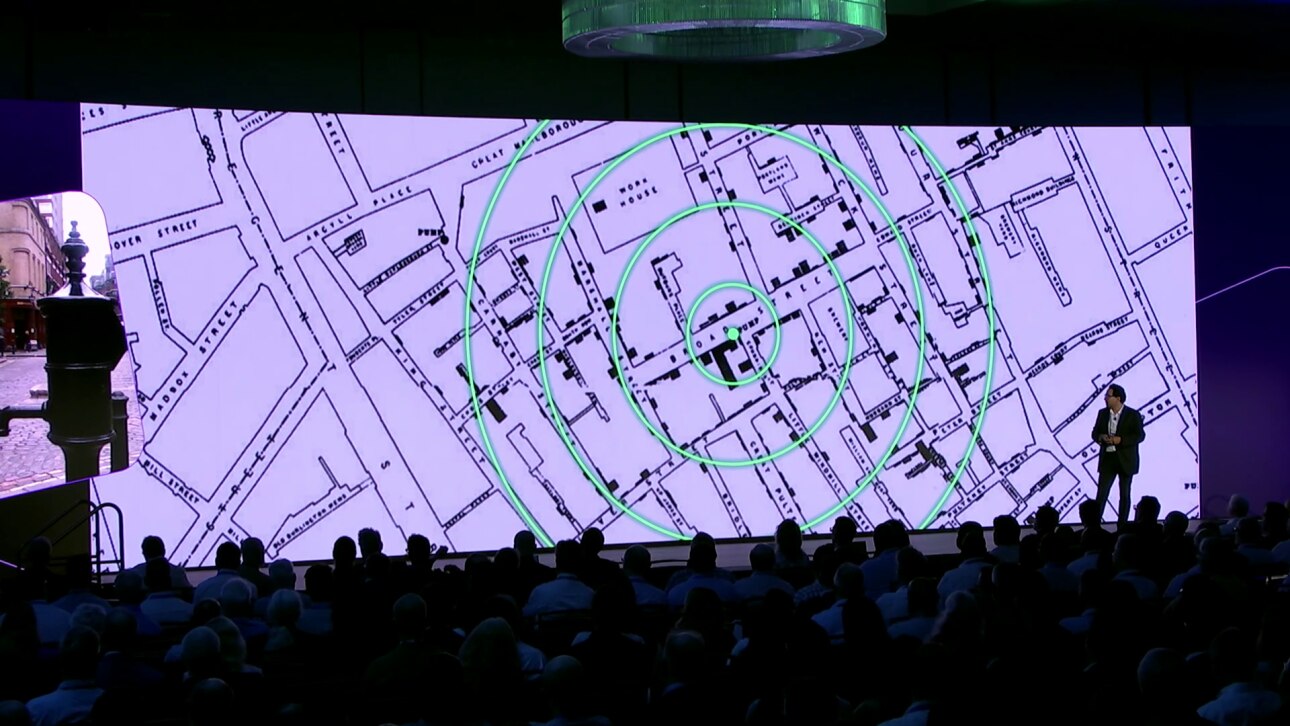

[2:25] Let me take you to London, not as it’s now, but maybe London how it was 150 years ago, to a gentleman called Jon Snow, generally considered the father of epidemiology. And Jon Snow had to deal with a cholera epidemic. And in those days, we didn’t know how cholera was spread as an infectious disease. Did it come from bad air? And there was something called the miasma theory. And some other people thought, well, maybe it’s actually some waterborne agent that is spread through drinking water, for example.

[2:45] And so Jon Snow looked at this problem and being a British empiricist he decided, well, let’s look at the data. And people didn’t speak about data in that way. So what he did is he really took the street map of central London and then decided, well, for each case of cholera I draw a little rectangle. And if there are more people suffering from cholera, the rectangle gets higher. And I think you can see how it looks over there. And so he invented the bar chart to visualize the data, and that’s literally, I’m told, the first bar chart ever drawn.

[3:15] And then he had another aspect to that thing. He wanted to test a hypothesis. Is cholera linked in some way to the spread of water? And so he looked at the data, and it seemed like these cases of cholera were all clustered around Broad Street, the little green dot that you see there. And he identified there was also a pump, a water pump, that you can still see to this day in London. I took this picture a few weeks ago.

[3:45] And so now he had the idea of going into a medical intervention. He had the authorities literally shut down the pump. And through that causal intervention he could then see that no new cholera cases arose. And the cholera epidemic was stopped.

[4:05] And so in one go he established public health and epidemiology in a very data driven way. He effectively started data science and data visualization. And he used causal interventions to manage public health at a systemic level.

[3:35] He also wanted to test a hypothesis. Is cholera linked in some way to the spread of water? And so he looked at the data, and it seemed like these cases of cholera were all clustered around Broad Street, the little green dot that you see there. And he identified there was also a pump, a water pump, that you can still see to this day in London. I took this picture a few weeks ago.

[4:25] And so how have we been faring on this journey? And so this is a question for you as an audience. Where are we in the journey to AI and digital healthcare? And I’m sure most of you will be familiar with these video games that have appeared over the past few decades. And I’m going to make my way over here.

And if you think about this, where’s digital health now, and where can it be in the future? I would like you to raise your hand when you think I’m close to where we are.

Are we in the Pong age of digital health? Raise your hands if you think it is. Are we at Atari levels? Are we doing CGA, which was the first proper color graphics? Are we at EGA?

[5:15] Okay, then we’re getting to better stuff. VGA. You know, now we’re in the 2010s. And now we’re in the 2020s. So thank you for that data collection effort with me. I agree with the majority of you, the majority of the weight, we are at the EGA level. We are just here, and we can still make it all the way there. And I hope we can make it as fast as this 1980s technology can do it today, or faster.

Why do we need to be fast? Well, I don’t think I need to mention that we are under severe strain in our healthcare systems. Be that in staff, be that in need for health and care, be that in costs.

And what we’re simply seeing is that over the past few years, the demand for health and care has been outstripping the supply that we can provide.

[6:10] And my hope and my goal of my career is to push the borders ahead, the boundaries. So we can make more and more of this unmet demand addressable by artificial intelligence.

And of course here we believe that AI is the solution. And most of us, you know, over the past decades thought about AI as a way of dealing and analyzing with data. And so that’s all of data science and all of the engineering.

[6:40] But really, if you start thinking about what’s the true value of AI, it’s that AI can do stuff for you that you don’t have to do anymore. And so we’re now talking about agency. And of course, we’ve all used ChatGPT. And now we’re seeing the wonders of this language technology being rolled out to facilitate life in the professions of healthcare through ambient intelligence.

[7:05] And so that’s generative AI. And we’re going to see also in the future more agentic AI. So AI systems that go out, you send them on an errand, and they come back and do stuff. Now that’s nice if you’re thinking about building AI systems as a problem where we’re looking at things that we’ve been doing inefficiently and we’re doing it now more efficiently with AI.

[7:30] But what I want to push you on, and what the purpose of my talk is, is to think about not how we can just do the old better, but how we can do things that we couldn’t imagine before by unlocking the power of AI. And so that’s what I call developing patient ready AI and really realize the full potential.

[7:52] And people say the full potential realized means we can increase life expectancy by one and a half years by catching preventable deaths. We can reduce dramatically burnouts of clinicians, and we can reduce the costs, and the satisfaction can be improved of the healthcare systems in our populations.

But there are a number of gaps that we need to address here. And the first gap I want to talk about is the observability gap.

[8:25] Only because you’re standing in front of a clinician doesn’t mean that they have a full insight of how you’re doing. The human body and the human context and experience is too rich for that. And yet, in many domains, we’re still operating medicine in a form of operation like we have been doing in the 19th century, in the days of Jon Snow. Let me explain.

[8:50] So a few years ago we started thinking about, can we think about using Gen AI methods to try to manage public health at the level of a country. And so of course the United Kingdom is composed of four countries, Scotland, England, Northern Ireland, and Wales. And I’ve drawn you up here the country of Wales, four million inhabitants.

And Wales is fairly unique because they’ve very early on started to digitize their data. So we have the complete linked patient records from 2009 to today for all primary care and all secondary care data.

[9:25] And we can do that because within the NHS patients are just in one system. And so we have every GP visit, we have every hospital visit, we have every single prescription picked up in a pharmacy.

And so we ask ourselves, can we now use that information to do something useful? For example, catching or predicting preventable life death situations.

[9:50] And the way we wanted to do that was, well, let’s use the data that we have available. Now of course over the past few years there were some beautiful studies, a lot of them in top notch US hospitals, where if you basically capture someone’s blood results and regular scans at a very high intensity level, you can fairly accurately predict if someone is going to get suddenly worse in the future.

[10:05] But can we do that at an affordable level where you don’t have to come in for a weekly blood test, simply from other data, from cheap data, data that’s not collected by a clinician or a professional but it’s collected by a secretary.

So we’re looking now at time stamps in administrative aspects of patient records. And so the idea was here that there may be a pattern in the information. And the challenge, what people will tell you if you look at primary care data, you don’t go to the doctor every week. You go for six, seven months, you don’t go, and then maybe you go more frequently if you have a problem. So the gaps were the issue.

And so what we started to look at, we simply looked at the time stamps of these records. And what you’re seeing here are just these rhythmic or arrhythmic patterns of interactions between patients and the healthcare system.

[11:00] And once you have millions of patient worth of records, you can look at these patterns. And to our surprise, we were able to predict with 80 percent accuracy, four out of five cases, if somebody needed to unexpectedly go to hospital in the next three months, purely from the time stamps, their age, and their gender and their postcode.

And that has put us in a very interesting situation that we have now a tool that can be used to potentially inform patients. Not sure if you want to do that with 80 percent accuracy. You can tell their general practitioner, hey, you may have a patient you may want to see earlier. Don’t keep them waiting so long. You can tell the hospitals, you’re going to have an increase, an uptick, in patients coming to you. Or you can talk to the public health authorities.

[11:55] So we’ve created a solution that suddenly prompted the question, how shall we best deploy that now. And this was thought not possible before because people didn’t imagine that as little information as the rhythms that you’re seeing of your healthcare interaction data carries so much information about your health state. Literally, there’s no other information we’re using.

And so we called this the Morse code of health. So that’s a way by which we can use administrative data in your healthcare records to start opening up this observability problem that we have on patients.

[12:25] Let’s look at other data maybe that’s collected in also other healthcare systems. Shopping data. We all go shopping. And when you shop very often you’re a member of some form of scheme where you’re swiping a card and they collect the data about your shopping information. This is known history.

But what we wanted to work at specifically is, can we use that to help with early diagnostics.

[12:55] And we focused on ovarian cancer, and ovarian cancer in women in London who went to the Royal Marsden Hospital, which is part of Imperial College Healthcare Trust.

And so we partnered with Tesco. That’s one of the big supermarket chains in the UK. People are very loyal there, so they keep shopping regularly. We recruited 150 women who were diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and they made their shopping data available to us by a cooperation with Tesco.

And then basically we did probably what the supermarkets did 30 years ago. We developed machine learning methods to analyze shopping baskets.

[13:35] And to our surprise, my collaborator James Flanagan and PhD student Kevin, we were able to find a marker that suggests that a change in shopping baskets eight months before diagnosis was systematically indicative of a future onset of ovarian cancer.

Now you may ask me, why is that. Can you explain it. Well, it’s a complex machine learning pattern that the machine recognizes. But the simple narrative is ovarian cancer gives you bloating. So in Britain, the baked beans goes out of the shopping basket. You stop buying cabbage. You buy something for irritable bowel syndrome, and so forth.

So this gives you an idea why this information about the shopping basket now carries a healthcare signal.

[14:15] Something that I don’t think most clinicians would have considered as a viable way of diagnosing. And if you go to them, show them your shopping receipt, it’s like, I guess you have this.

But once you have data available at scale, and we’re now expanding this collaboration with Tesco to look at other forms of diseases, we can really start opening up completely new ways about thinking about medically relevant information that is out there. And that’s another step to close this observability gap.

[14:45] Another important challenge is, well, what do we do the whole day. And I remember when my grandmother developed Parkinson’s, I could notice that she was acting differently. There were subtle changes. It was very hard to put a finger on that. And it was not the tremor at the time. It was changes in the routine.

So what we did is, around 2010, we set up what we call living labs. So we basically converted the whole corridor of our laboratories into a flat and invited people into an apartment to live in there for days on end.

[15:20] And we collected all sorts of data. This is a ten year old video that you’re showing here. So we collected the movement of the skeleton, measuring eye movements, everything was annotated, and we basically built a database.

So it’s a bit like when you had genes and you did genomics to sequence the genome of the human. We’ve done that for behavior. And ethology is the science of behavior. So we collected the human ethome. And we’ve collected thousands of data points that way.

[15:55] And of course now once you have loads of data about movement of people, you can start using that, for example, for diagnostic purposes. So here on the left you see children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. This is a boy aged seven at the time that is going through a standardized clinical assessment, standing on one leg, walking for six minutes on end.

And it’s a fairly cruel way of measuring effectiveness of mobility of children that are going to become paralyzed and die by the age of 20 or 24. It’s a brutal test

[16:35] And now effectively, if you’re a company who wants to develop a treatment, a disease modifying treatment for that, you need to basically show that in all these assessments the children have not substantially decreased in performance.

These assessments are so crude that there are anecdotes of children having a bad day in school, then going to the clinic for assessment. They walked 50 meters less or they stood for two seconds less on one leg. These are very crude ways of assessing disease. They’re 19th century methods of assessing disease.

[17:10] And on the left you see the same boys simply playing at home, where we’ve captured their motion data doing whatever they want to do in their context, assessing what’s important to them for them.

So we then took all this data that we collected from our human ethome project, and we did effectively what people who built large language models do. You harvest all the data, all English language text off the internet, you throw it into a machine, and the machine learns something about the structure and meaning of human language

[17:45] And so we did the same thing for human movements. And so out of this model, we could then basically feed information back about kids doing the clinical assessment in the clinic or kids playing at home, because for the machine, it didn’t actually matter.

It doesn’t matter to ChatGPT if you put in an X message or a Shakespeare sonnet. It can digest and understand both.

[18:20] And lo and behold, we were able to discover equivalents of what you would call tokens in language models for behavior that we can interpret and clinically look at. And what you can then do is you can basically digitize human behavior and basically create a string of tokens that then a machine can start digesting and understanding.

[18:45] And so what’s very important here is we can now basically predict the disease course for every single kid with twice the precision that’s possible with the FDA approved gold standard methods of disease.

What’s more important, if you want to develop pharma, is that you need to run clinical trials to determine whether your drug works. And with this technology, we can do that in half the time because the method is more sensitive to change and with a fraction of the population.

[19:20] So here you see the curve that you need. How many individuals do you need to get a certain precision. And at the moment, FDA approved minimum is 60 patients for a trial in a rare disease where it’s hard to recruit kids. And we can get the same precision with nine kids.

So the trial is a fifth of the size. And all of a sudden, by making trials faster and less expensive, you’re taking risk out. And so we can hope that we see more disease modifying treatments now emerging.

[19:55] And the method was so effective that we thought, can we apply that to other domains, not just children’s diseases of muscles. So we started working on Friedreich’s ataxia, which is a disease that affects your mitochondria. And it’s a genetic disease. So it means that the way your genes produce proteins is upset, and your protein levels vary, and that’s what makes you sick. And if you want to study that, or if you want to monitor patients, you effectively need to take a blood test and then go through the whole molecular biology to then measure how much of that protein is in that person at the moment.

[20:07] And that’s a slow and expensive process. And so we took the exact same pipeline and we fed that through the system. And lo and behold, the identical pipeline was able. Remember, it’s just like language models. It doesn’t matter whether it’s an English comedy or an American drama. It can understand just the text.

And we could use that to effectively reconstruct the rate of gene expression that a patient had on a given day, equivalent to the blood test, by just using wearable data that was collecting their motion. And to my chagrin, I can say that the FDA approved biomarkers could not reconstruct the gene expression level. So it’s not a trivial problem.

So all of a sudden, we can now use variables, things that measure how you are doing today, not comparing you to some average after you’ve gone to a clinic, to be as sensitive as measuring the activity of single genes in your body. That’s the power that we have by using AI systematically to unlock information about our health that’s there. That’s how we can close, or start closing, the observability gap.

[21:20] So now we know what you have. We know how you’re doing. So let’s do something about it. That’s where the clinical work really starts. You want to make patients better once you know what they have.

And this has been slightly overlooked a bit in the AI for healthcare domain. Of course, all the quick wins were in diagnosis, especially in radiology. The data was there, it was labeled, and you could just deep learn the problem to its end.

And there are, of course, challenges when you’re thinking about AI for treatment. Most of these problems are problems of cognition. So if you’re a radiologist looking at a scan, it’s a problem of perception. If you’re putting a stethoscope to the chest to hear if the lungs are free, it’s a problem of audition. It’s all perceptual problems.

But once we start thinking about treating patients, it’s a problem of cognition, because you need to plan, adjust, and manage what you’re doing.

[22:25] So if we want to push AI technology here, we need to think about AI systems that are agentic in nature, that can explore different paths without having to execute them, and then basically pick the best path that you want to take and go along.

So that’s really what agentic AI is. Give a system agency to do something. Now you may say, well, okay, Aldo, it’s great if a system goes out and explores what it can do for a patient, but they may actually be rather dangerous.

By the way, that’s how we’re training self driving cars. First in the simulator and then in the real world. But okay, so how can we do it better in healthcare.

So here we started working around 2015 on methods that we applied to the challenge of sepsis.

[23:05] Sepsis, of course, the biggest killer. We know how to treat sepsis. You can give patients antibiotics. The problem is your cardiovascular system collapses and shuts down before the antibiotics work.

So you need to prop up the cardiovascular system, and you can do that by managing that by prescribing different dosages of drugs. Without going into details, these are vasopressors and IV fluids to keep the heart pumping and the fluids flowing.

So what we did is we walked into Imperial College Healthcare Trust, recruited 45 intensive care clinicians, pulled 30 patients’ worth of records out of the system, put a patient record at a certain moment in time, and asked the clinician, what would you prescribe.

And what you’re getting is a spread of over 500 percent in the dosage of one drug across a population of 45 clinicians. And for the vasopressors, the spread is narrower, but there was roughly a 50/50 chance if the drug was prescribed at all or not.

[24:10] Now, I’m not a medic, and I do know that these are very difficult decisions. They’re really sitting there and thinking for minutes, sweating on their eyebrows, to think about what dosage to give.

What we’re seeing here is the challenge that it’s very hard to define what a good treatment is. And not all these treatments can be actually good.

And so what we developed were AI methods that learned from operational historical data of how the patient was doing and what treatment was given, to systematically find better strategies of treating patients.

You can imagine that a bit like the chess game. If you don’t know about chess, you can just observe chess players for a long time and you will get the rules. You will see that they make some moves, and then at some point you realize maybe another sequence of moves would have been better.

[25:00] And we’ve done this with mining 80,000 healthcare records, patients in ICU, and building a system that has been called the AI clinician by now.

And this is a 10 year journey, and it’s been rolled out into a number of hospitals in London, where we’re treating the system, and it’s de facto the first semi autonomous system for treating patients that was entirely learned out of data. There was no tweaking by a biomedical engineer. And we’re now taking it to other domains of medicine, to pediatrics and so forth.

Now that’s nice, and that’s history. Why is it important. Why am I showing you that now.

[25:45] Because now we had the challenge that if I want to see impact of this, the papers are published, but it doesn’t mean that I’ve helped a patient with that. We needed to take that into practice.

And so this is when I started to become interested and active in regulation of AI for healthcare, and ultimately in policy and regulation of AI for healthcare. Because if you want to effect a change, you need to enable regulation to be proactive with the changes that you have, and not just reacting to what’s happening.

So we need to address the translation gap.

[26:20] And so one of the first things that we did is we wanted to make it quantitative, an assessment of how does the AI impact the system.

So we took wards in an intensive care room in Imperial College St Mary’s Hospital and converted it into a fully sensorized space. We know how to do that. I showed you how we did that a decade ago.

What you’re seeing now is a clinician who came in, visited the intensive care ward, and interacted with the patient.

[26:55] And effectively, we devised a protocol that allows us to measure how big was the impact of the AI on the clinical decision.

We show you the patient’s information. We ask the clinician, what would you dose that patient. Then we show what the AI would have done. And then you ask the clinician, do you want to change your decision on the dosages of the drug.

And then you can measure. If they don’t change at all, then they trust themselves more than the AI. If they change a bit, then they trust the AI a bit. If they change a lot, then they trust the AI a lot.

And so we have what we call this trust shift, as a way of systematically starting to measure and evaluate the impact of AI technologies in the clinical room.

[27:40] And we also asked them, would you stop the AI system because it’s crazy or something like that.

So now I’m going to show you the same video again, but with extra data superimposed. We had done the eye tracking on the clinicians. So now you’re seeing literally where they’re looking for every second.

The heat maps tell you where they’re paying more attention when they’re ingesting information about the patient.

And that’s now the AI. Well, it’s nothing else but the screen that tells you, oh, this is what you should prescribe. And these are four different ways of motivating my explanation.

[28:20] And here it becomes very interesting. So the first thing was, well, 80 percent of the time clinicians adjusted their decision towards the AI. That’s interesting. And it was independent whether they believed in AI or they were very AI affine. We did the sociology of that with this questionnaire.

The other important fact is they didn’t pay a lot of attention to the explanation the AI gave. And that was surprising, because everyone tells you how important explainability is for AI. They didn’t care so much.

In fact, we found cases where when you interviewed the clinician afterward and said, what made your decision sway. They said, well, you know, Aldo, I think this explanation really convinced me. And then we went back and looked at the eye tracking, and we saw they never looked at the explanation.

[29:00] So in humans, we call that confabulation, when you’re fitting the reality consciously or subconsciously to what you have done. And that’s what we learn in college, of course.

But it’s a bit unfair when people complain about hallucination by generative AI, and effectively we have a very similar effect going on in the human.

So I’m here to advocate for the AI, of course. But other things that were interesting was the factor, and here we’re talking really about human AI cooperation. So the nurse that you saw, it’s actually my PhD student who is the clinician himself, would flip a coin, and whenever the doctor made a decision, unseen to the doctor, he flipped the coin and would then ask the doctor, are you sure doctor. That’s all that he said.

And in 20 percent of cases, the clinician switched the decision.

[29:45] And so this impact was in some cases bigger than the impact of the AI giving a recommendation. So now it means we need to study the interaction between not just the AI and the human doctor, but the human-human interaction is part of the human-AI interaction.

And of course this is known. You can read that in textbooks and studies done in the clinical domain. But because I’m an engineer, because I’m a computer scientist, I actually have to measure it so I can compare how my engineered system, or my AI system, compares to that.

[30:16] And so we’ve started to open up a number of things. Basically, in a nutshell, the main conclusion we’re drawing out of here for clinical decision support systems, as well as for potentially future fully autonomous medical treatment systems, is that clinicians really want options of what to do. It’s nice to have an explanation, but it’s the options that you want.

And I always compare that a bit to the situation room, where the president goes around and asks his generals what shall we do, and he wants to know the options. He doesn’t want to know why and the long history behind that. And this has some impact, to go all the way back to the mathematics behind the models we developed, because if you have to offer options and not just the best solution, you need to redesign a bunch of things.

[31:04] And so there’s another gap in the treatment that I foresee, and that has to do with the fact of how we’re training AI systems and how we’re letting them out in the real world.

So, at the moment, if you’re a clinician, you go to medical school, you pass your exams, you get board certified, and then we let you out into the real world. And you learn your whole life, and you become a better doctor from experience and interactions. That’s great.

What happens when you have a software as a medical device that is an AI. Well, the moment you’re certified by the regulator, we freeze your brain and forbid you to learn anything new, because we don’t want you to do something else but what you have been designed for. Right. I can get it. My pacemaker shouldn’t make a samba, it should pace at a steady rhythm.

But really AI is built to learn, and you want AI systems to learn from the interactions with the clinicians and the patients that you are having.

[32:04] You may want to learn about new diseases that come up and adapt yourself to them. And you want to learn about the specifics and quirks of the deployed environment. Are you in a rural setting. Are you in a central city setting. What treatments are working better in a hospital than others.

And of course there are ways that we can think about that to make that properly workable. So you can, for example, send information back about what the AI was doing to the manufacturer, and then the manufacturer can recertify or adapt AI, but then you need to deal with information governance about these systems.

So there are solutions about that, and I’m glad that at least in the UK we’re having these conversations about how to enable lifelong learning of AI systems. But still the default answer globally is we freeze the brain of junior doctors when they come into hospital and make them learn and practice what they did whenever they got their medical degree. That’s what we’re reducing AI to.

[33:05] So with that, I’ve given you, I think, a number of flavors of how we can address changes that are required to achieve the full potential.

And my hope is that at some point in the future, we’ll have something that I call a programmable healthcare system, or software defined healthcare system, where we have the ability to configure, deploy, evaluate approaches and technologies, or human and pharmaceutical and other forms of intervention, in an integrated way, as simple as we can configure systems now, and hopefully in the speed and in the level of adaptation that we need.

I think it also becomes clear that this is not possible if we don’t have a flexible data governance that is proactive and not reactive. And it’s only possible if you have also a flexible data infrastructure that allows you to bring this together. And I think that’s why I’m very grateful to have been invited here to speak to you about this.

[34:07] When we’re thinking about where is AI and health going is that we need to think about partnerships and working together, not just across institutions but across countries.

So you may think that the 65 million, 70 million patients’ worth of record in the NHS that are going to be brought together into a large national data library are a big amount of data. They’re not. Again, compare when generative AI in the language domain became powerful, once we had absorbed all English text on the internet and started digesting more text out of books and so forth.

We need to work together across boundaries and borders to bring this data together.

[34:45] We need to think about making AI sustainable, not just because there’s a tremendous cost on hardware. Certain companies bought two thirds of the available GPUs last year to push their agenda forward. How can we make sure that other domains, especially in healthcare, get serviced by appropriate AI technology that can transform data into a meaningful product and solution.

We need to talk about energy and the cost of energy. I’m not too concerned about that, because if you think about the power that we’re unlocking with AI, it will compensate for that.

But ultimately, we need to think about the sociology of the problem. And the sociology of the problem is actually what I find, and I’ve been working in Switzerland, in Germany, in many different countries doing healthcare for AI research. It’s seldom the law that’s the biggest hurdle, or it’s not the technology, and it’s not the clinical side that is the limitation. It’s the mentality of people in their heads, how they’re approaching that.

[35:47] And so my hope is that with the methods that I showed you in the near future, we can really start thinking about holistic health.

And I don’t mean it in an esoteric way. I mean it integrating all forms of data that we’re already creating, rendering that useful, and use an AI system to help guide interventions at the clinical level, at your behavior, influencing that, or have even your environment do ambient interventions.

We can even think about ambient therapeutics in the future. So really we want an AI sharper that guides us to the summit of what AI can do.

[36:19] And so as part of that journey, we have launched the Nightingale AI initiative two months ago. And the idea here is to render the world’s healthcare data useful to build the world’s true first large health model.

You’ve seen large language models in health. That’s a bit like an English major learning to read and then reading medical texts and reasoning based on that. We want to have a system that reasons like a clinician.

So we want to train it on the entire NHS’s healthcare data, all the available scientific databases and the literature. And we found a large consortium of institutions across the UK and Europe to support us. And as of last month, we have also onboarded two California institutions. So we’re really working very hard towards that goal.

[37:04] So to come to an end, what lessons can we learn. I think very often people are talking about we need to change the system. We need to plan about how to change the system.

In my experience, the normative power of creating a factual solution that does something like we’ve done in Wales, you tell people this is the tool, this is what your tool tells you, is much more powerful in affecting change than just talking about it.

We need to think systematically about how we use this idea that machine learning can learn things we can’t even think about because we’re limited in our human ways.

[37:43] We shouldn’t just think about collecting data and libraries, think like librarians. I take the glasses up for this. But instead think more like people who are building factories and tools that are powered by data. But it’s actually the application that matters.

I hope I’ve convinced you that healthcare impact is not just MD business, not just medical business. We can use shopping data, for example, to bring things together. We need to think it’s much wider, and thanks to the power of AI and with the right ecosystem, we can bring this data together.

And last not least, you really need to think from day one on people in change management. And that’s the computer scientist that preferred to spend time with his computers over people in his youth who’s telling you that.

[38:20] I think that’s the most fundamental limitation that we’re facing when we’re thinking about the future of AI.

And so with that, I’m leaving you with a beautiful piece of art that shows you a volleyball player. And very often when we’re in these data driven domains, we’re just tidying everything up and you have this nice collection of things, but sort of the beauty of the whole is lost.

And what I hope I can convince you with is that with the power of AI and the power of a data ecosystem, we can put these individual bits back together into one whole picture that is beautiful.

Thank you.